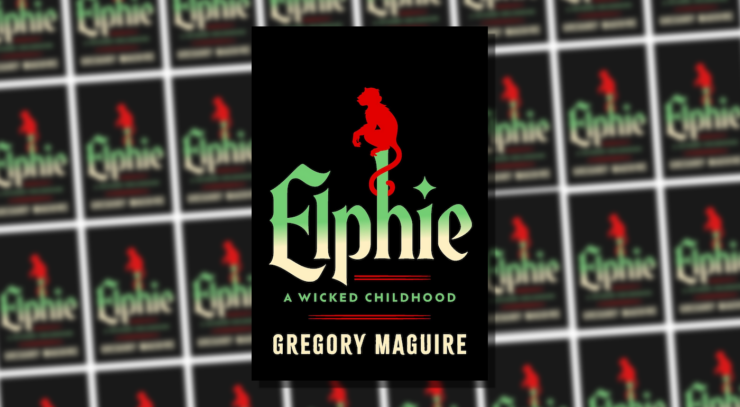

If there is a downside to Elphie, the latest novel from Wicked author Gregory Maguire, it’s that reading it left me wanting to sink into a reread of the entire Wicked Years series, from the first appearance of Elphaba Thropp to the (temporary) end of her granddaughter Rain’s story in Out of Oz. After that book, Rain eventually went on to star in her own trilogy of novels, Maguire’s Another Day series.

I have no sense of how many people have read those books, but if you have, you know that Maguire, as he continues these tales of green girls and strange magic, has never done the predictable or obvious thing. The Another Day novels are meandering, lush, with the feeling both of whims followed and something specific to say. Maguire’s trips back to Oz (and nearby locales) have always felt like explorations, forays into rich and unmappable territory. They are always about people living in complicated times, trying to figure themselves and the world out as best they can. It’s rarely easy.

And it is no easier when you are quite small.

Elphie takes place between the first two parts of Wicked, after our green girl says “horrors” and before she goes to Shiz. It finds the Thropp family deep in Quadling Country, damp and grumbling, disconnected from one another and the rest of the world. Frex Thropp seeks the people of the glassblower Turtle Heart, who was the lover of both Frex and his wife, Melena. Frex, a minister, wants to atone for Turtle Heart’s murder (which he did not cause, yet feels responsible for). If he can make some converts to the worship of the Unnamed God along the way, all the better.

Meanwhile, small, green Elphie is practically in danger of blending in with the landscape. Maguire’s Quadling Country is far from L. Frank Baum’s chaotic locale, and if I have a complaint about it, it’s that it can seem a sort of vague stand-in for any lush, jungle-covered land that has faced the forces of would-be modernity and so-called civilization. The Emerald City has come with its yellow bricks and its desire to drain the swamps and uncover the rubies secreted away beneath them. The people are not happy about it.

These happenings hover somewhat in the background, though, because this story belongs to Elphie, and she’s all of “three and spare change, maybe four” when it begins. Nessarose is a baby. The book is divided into four sections, each with the feel of a sort of detailed Polaroid, a moment in time, gauzy and imperfectly remembered.

That imperfection is intentional. Maguire, from the get-go, assumes a narrative voice that is knowing and tart—and also dismissive of the idea that one can really know, well, much of anything for certain. These are the moments that shaped Elphaba; the technicalities are irrelevant. Was there a polter-monkey, and did he lead her mother’s spirit away? What of the marsh-plum seven(ish)-year-old Elphie claimed to hex? What can you remember precisely about your childhood, and what does precision matter if those imperfect memories made you who you are?

Buy the Book

Elphie

In a recent interview, Maguire said, “I really do believe that who we are as adults is rooted in who we were as children and how we survived whatever it was that life threw at us in childhood.” Elphie explores what the world offered or threw at its title character before she went to college. Maguire manages the balancing act required by prequels: the art of exploring without over-explaining. (Elphie’s excellent voice might seem a nod to the musical, but eight pages into Wicked, Frex thinks that his daughter will be a singing child.) There is no one key moment that defines this future witch. Nothing is that simple. It’s what she learns, piece by piece, that matters.

Melena dies giving birth to Shell; Frex, never the cuddliest father, grows more distant in direct proportion to the number of congregants he attracts. The fact that there has never been a truly functional adult in Elphie’s life for long is made expansively clear: Nanny is, as ever, a delight, but her perspective is limited. Other important adults come and go. In the town of Ovvels, a reluctant teen Elphie is taken under the wing of a shopkeeper, Unger Bi’ix, who teaches her, in essence, how to exist in the adult world. She works for him, and she learns, and her quick mind is obvious. Unger knows her future is not to be a shopgirl, but he also sees that she needs something her family can’t give her. The tough-love relationship between the two of them is a warm delight against her father’s religious demands and “obligatory accommodation,” as Elphie thinks of her family dynamic.

What feels the most definitive of the woman we meet in Wicked is not so much something that happens as something that doesn’t: No one tells Elphie about Animals, the sentient, talking creatures that have such a troubled existence in Oz. Her anger over her ignorance is transformative—the existence of Animals, the fact that people kept that from her, opens her eyes to the world and how much else she could be missing. It is sort of like a weird little gremlin child discovering punk rock, but in a very Ozian way. “She’s been kept in a prison of her own ignorance,” Maguire writes when 13-year-old Elphie meets a pair of delightful Dwarf Bears. One says to her, later, “You’re an idea that I didn’t have before I saw you. Ideas make us jump. They shift us from before to after.” You might call this book a series of ideas, a series of scenes that shift Elphie, young and growing, from so many befores to so many afters.

Elphie will not be for everyone. It is light on plot and heavy on mood, on questions and observations, on those instances in a life where a connection is made or snaps. It is a sort of impressionist portrait of a curious and lonely child, one who seeks knowledge and understanding more than she seeks emotional connection—because what example of the latter has she ever been given?

It is also, like Wicked, a book about grief and loss. In a sort of flash-forward, Maguire writes of adult Elphaba, “She will think of herself as having adored Nessarose and cared for her sister always. She will mourn Nessa’s death without recognizing that guilt is part of the chemical composition of grief.”

This line knocked me sideways. For years I associated Wicked with grief simply because of the time of my life in which I read and reread it like a talisman. Years later, I went back and realized how much grief—and, yes, guilt—is there on the page, and how constantly and powerfully that spoke to me. The existence of the musical can make it easy to forget how much time book-Elphaba spends at Kiamo Ko, grieving and guilty. As an adult, Elphaba knows what loss is. As a child, she has a sort of heartbreaking obliviousness, understandable and terrible at once. Quadlings have a process for dealing with grief. The Thropps—like so many of us—do not. They simply do not deal. From her mother’s death to her father’s distance, Elphie is left more and more alone. You can see exactly how she comes to do what she does after the tragedy in the Emerald City.

But that’s much later. Maguire has long had a light touch about his creation. He dedicates Elphie to Idina Menzel, Cynthia Erivo, “and for all the Elphabas, past and to come.” The way he tells this story—the maybes and the uncertainties, the pointed disinterest in how or when it “really” happened—is yet another way of being both hands on and hands off. This is his version. The narrator says as much, near the end, an intimate “I” leaping into the text, briefly. Yet it feels like he wants us to have our own, too. These are some scenes that made Elphaba Thropp who she was when she got to Shiz. These are the damp and formative years, the years of learning and fighting and being angry and wanting more, more, but not even knowing what that more was, sometimes. But there is still space held for your version, too—for all our Elphies.

Elphie is published by William Morrow.